Have we entered a new paradigm in which growth, inflation and value investing are dead? Various indicators might have us believe this is the case.

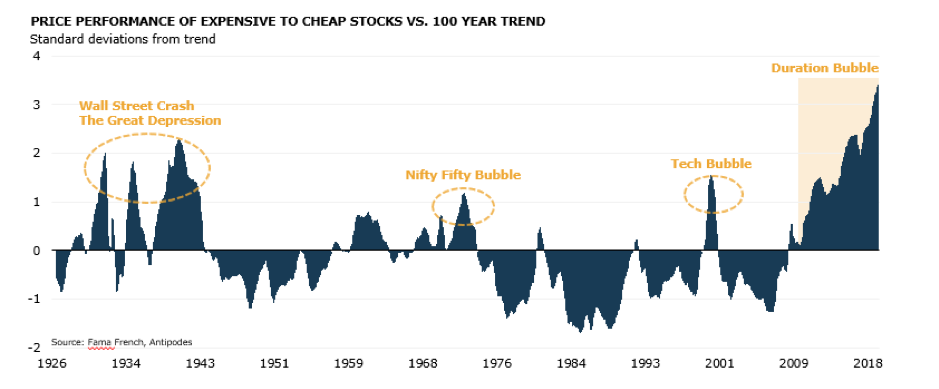

The chart below is one. It shows the monthly performance of a growth index, relative to its long-term trend. Based on Fama French data, it measures the price performance of the most expensive stocks relative to the cheapest stocks. You can see just how extreme the price performance of expensive stocks versus cheap stocks has become in the period we’ve labelled ‘the duration bubble’.

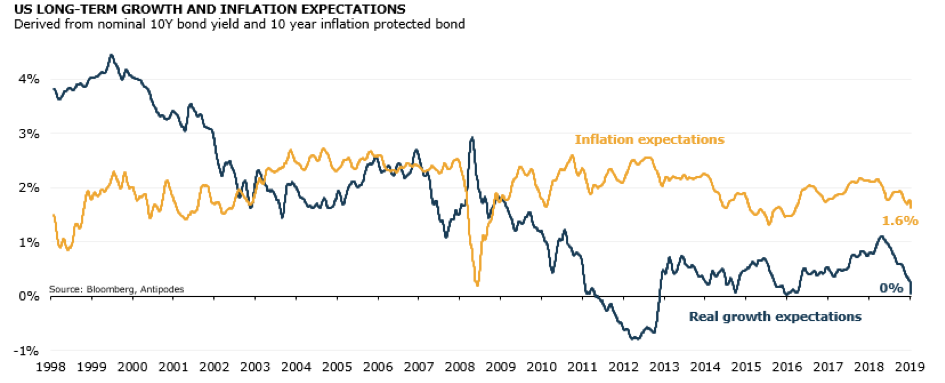

Another indicator – the extraordinary moves in the bond market, which are signalling limited long-term economic growth. Take a look at the US 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Security (TIPS). It’s a government bond indexed to inflation to protect investors against rising prices. As inflation rises, the price of this bond also rises.

On the following chart, you can see the yield on the TIPS (blue line) is zero. The yield on the nominal 10-year bond is around 1.6% (orange line). We can, therefore, infer that inflation expectations are indeed around 1.6%.

With the yield on the TIPS at zero we can further infer that investors’ expectations regarding economic activity in the US over the next ten years have completely collapsed.

Yes, there are headwinds, but to assume no economic growth for the next ten years seems extreme.

Why ‘The Duration Bubble’?

In a ‘zero-growth’ environment, one would expect investors to chase yield. But this is not happening. If this was the case, investors would be crowding into high dividend yielding stocks like European banks, which have a 7% dividend yield, or any number of other cyclical sectors. They’re not.

Instead, we believe investors are chasing ‘duration’.

What is duration? Duration is how long it will take a company to cover its starting valuation with its future cash flows. The higher the starting multiple (or lower the earnings yield), the higher the implied growth or financial leverage in the business, and therefore the higher duration (it will take longer to repay the starting valuation).

When rates approach zero the valuation of long duration stocks benefits disproportionately, relative to the rest of the market. The closer you get to zero the more extreme this becomes. It’s worth emphasising it’s not as rates fall, it’s as rates fall to near zero.

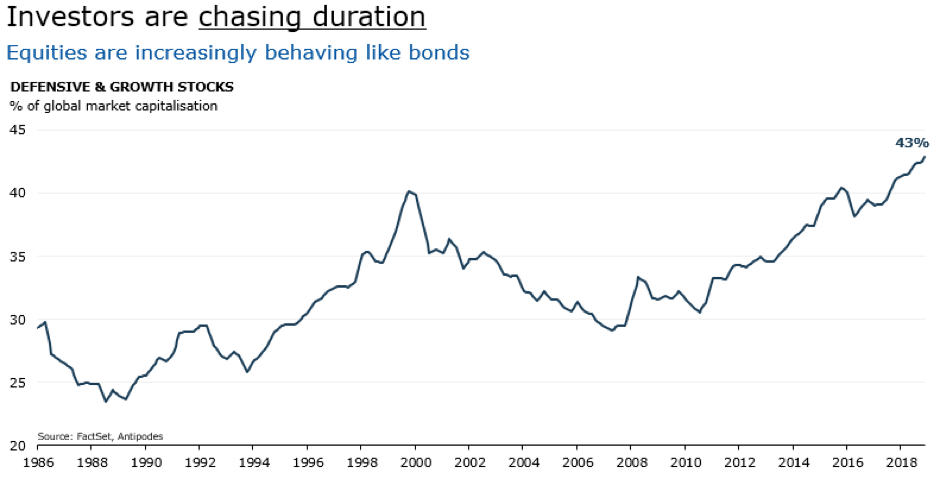

This current environment favours bond proxies and structural growth stocks, we can see the proof of this from the chart below. The defensive and growth parts of the market have now grown to account for almost 50% of the global market cap. This is the largest it has ever been in almost 35 years. Equities are increasingly behaving like bonds as the market has bid up the price of long duration assets like consumer staples, medical devices, software and internet.

Conversely, the more cyclical parts of the market have become cheap relative to their long-term history. This is despite many of these businesses growing free cash flows at a very respectable rate. These businesses now trade on low multiples, so it doesn’t take long to recover the starting valuation (they have become short duration assets). This doesn’t mean these businesses are impaired, though we have no doubt in a low-rate environment free money is eroding scale as a barrier to entry. We expect to see more value traps going forward.

With growth expected to be zero we believe the market will be sensitive to small beats in economic data. This will not only be bad for bonds but also bond-like equities.

Can this thirst for duration continue?

With central banks committed to monetary stimulus and bonds telling us that we are living in a world with no growth, what changes the chase for long duration assets?

One of the consequences of Quantitative Easing is that it has stimulated asset prices but not activity, which has led to ever widening wealth differentials. The consequence of this has been a rise in populism. Growing global populism – we can see it in Brexit, Italy, Hong Kong and Argentina – has led to a de-rating of European and Emerging Market equities. But the same risks are building in the US as the election cycle moves into full swing.

A rise in populism leads to protectionist policies (e.g. trade wars) and greater regulation which has a feedback loop into weaker growth and more populism. Central banks respond with monetary policy which increasingly seems to be failing to create demand or encourage banks to lend, and hence feeds more populism.

If monetary policy doesn’t work, where does this lead us?

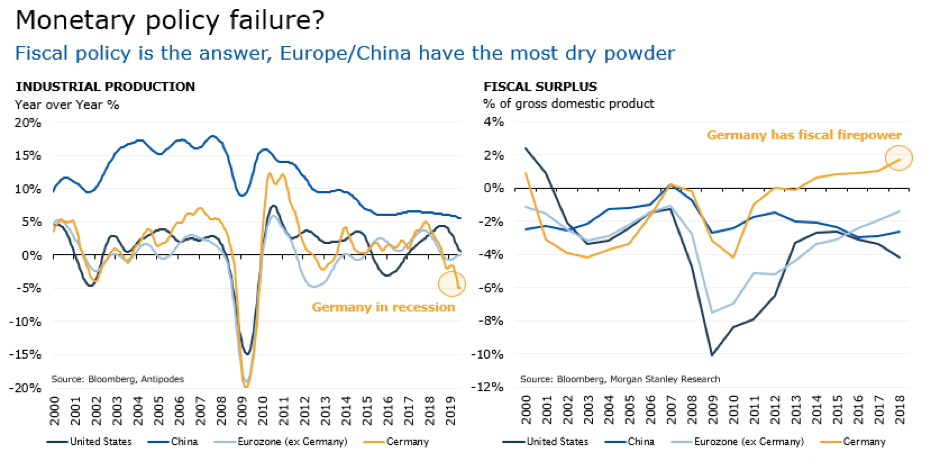

We believe countries will look towards creating fiscal stimulus, as we have already seen in the US. Europe and China have the most dry powder.

Germany used to be the healthy part of Europe but is now underperforming the rest of Europe on account of the global trade slowdown. Germany (and Europe more broadly) may be prepared to loosen its grip now that their economy is heading into a recession, and they’ve got the firepower to stimulate their domestic economy. We’ve started to hear discussion from European Governments regarding stimulus e.g. The Green New Deal, a plan to transition to zero greenhouse gas emissions, which will require a major green-related infrastructure spending cycle.

We think investors should be open-minded to fiscal policy being the answer, and how this may impact the economies that have the firepower to stimulate

So, what needs to be considered when investing in the ‘duration bubble’?

- Central bank impotence and the subsequent rise in populism will lead to fiscal stimulus.

- Europe and China have the firepower to stimulate, while European and Emerging Market domestic exposures are priced for a recession.

- Tailwind from stimulus in the US is fading.

- Long duration stocks are priced at a premium, while cyclicals are priced for a recession.

We believe true quality and growth is still available, investors just need to look into less obvious parts of the market to find it.