Inflation is no longer the elephant in the room, it’s the talk of the town. Particularly after the US Federal Reserve’s latest meeting minutes were released last week.

Long story short, they talked about the potential to talk about reining in bond-buying efforts at future meetings. Planning to plan you might call it, yet it was enough to indicate not all Fed officials have their head in the sand when it comes to inflation.

The market is expecting near-term inflation to rise, but the common rhetoric is that this is transitory.

We think we could see an inflation surprise in the coming months which the market is not prepared for and believe inflation could in fact trend higher for longer.

Wages are rising

During the fortnight, McDonalds announced it would lift its hourly wage by 10% in a bid to attract more workers. There have been similar wage rise announcements from Walmart, CostCo, Bank of America. Even Amazon has made a commitment to lift wages for more than 500,000 employees.

Today’s unemployment benefit in the US is around 30% higher than the minimum wage, so you can see why finding staff isn’t easy at the moment.

Supply chains are shifting

Along with pressure on the minimum wage, Chinese demographics and the re-shoring of supply chains can play a major part in longer term inflation.

The common thread we’re seeing across the US and Europe is that pressure is building in supply chains – from raw materials, energy, transport and labour.

China has been a global deflationary force when it comes to manufactured goods. Integration into the world economy saw an effective one-time doubling of the global supply of labour. In 1990, this labour in China was 60% cheaper than the US. By 2018, the labour gap had fallen to 20% cheaper. You get the drift. This pool of low-cost labour in China is materially falling as incomes rise.

As this labour discount continues to narrow, we may see an inflection point in the coming decade in which the risks of globalisation are no longer offset by the rewards.

And that’s not all that’s changing in China. China is starting to prioritise decarbonisation over capacity, and weak and inefficient state-owned enterprises are being weaned off government aid. This can have a more structural impact on the price of certain raw materials – something we don’t think is getting enough attention.

The question is, can other emerging nations fill the void? China had a unified national strategy when it came to industrialisation, as well as access to cheap, and seeming limitless, capital. It’s difficult to see how countries like India or those in Africa can replicate China’s model.

Not only is China’s low-cost labour disappearing, but populism along with geo-political tension is prompting Governments and companies to bring parts of their supply chains home. COVID brought to the fore risks relying on a very lean, just-in-time inventory system that’s dependent on manufacturing capacity in other parts of the world.

We dive into this in further detail in the latest episode of our Good Value podcast, where we examine the arguments for and against inflation.

Positioning for inflation

As inflation rises investors should focus on resilient businesses that are market leaders – companies which can pass on higher costs to customers.

Examples in the APL portfolio include Lowe’s, the number two home improvement chain in the US and Yum China, the largest quick service restaurant franchise in China.

Dominant brands like these will be in a stronger position to protect their profitability as costs rise.

Bond yields will respond to rising inflation. Investors need to be careful what they pay for growth – growth traps will be revealed in a higher inflation and higher yield environment.

It’s why we believe pragmatic value is an effective investment style in the current environment.

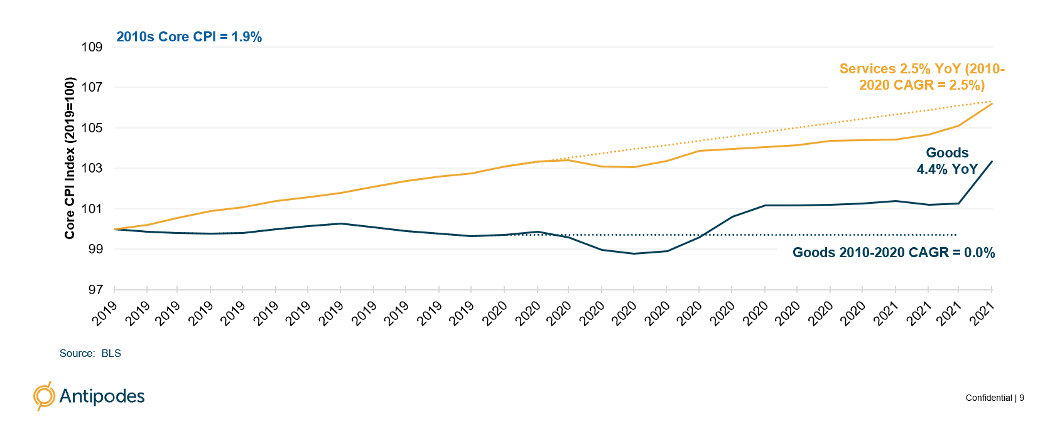

A chart in focus | Inflation of goods vs services

Service sector inflation had been running below trend as activities like travel, eating out and entertainment were a big source of underspending in 2020. But the goods sector is inflating thanks to disruptions to supply chains, and rising raw material, energy, transport and labour costs.

Spending on services is normalising as economies fully reopen. And goods inflation has the potential to remain sticky thanks to re-shoring of supply chains, China’s shrinking pool of low-cost labour and pressure on the minimum wage from unemployment benefits and rising populism.