Who would have thought an oil price contract could go negative? This is in fact a reality that has unfolded over the past few weeks.

To understand the dynamic behind ‘negative oil’ we must look at the backdrop in which this had unfolded. The fight against COVID-19 has seen entire economies and communities shutdown, causing an unprecedented decline in oil demand. During the second quarter of 2020, we’re now expecting oil demand to be down around 15 million barrels a day (or 16% y/y). For context, during the worst period of the GFC we saw a draw down in demand of just under 3 million barrels a day.

But there’s been another major factor behind the oil price shock – the breakdown of the OPEC+ alliance.

As COVID-19 containment measures were just beginning to cripple economies in early March, the Saudi Arabia-led OPEC alliance failed to come to an agreement with Russia on oil production cuts. This prompted OPEC to lift all its own production limits as the worst of the COVID-19 crisis was hitting. This resulted in storage facilities filling rapidly, particularly in the US.

This has led to the unthinkable situation when WTI oil futures traded at a negative price. The reason for this is somewhat technical in nature. WTI futures must be physically settled rather than cash settled with the delivery point at Cushing, Oklahoma, where all storage was either full or already booked out. Given they had nowhere to put the oil, buyers were unwilling to take the oil at any price.

The sell off in oil has largely been at the front end of the futures curve with little change in long term price expectations. Indeed we believe the degree of capex cuts brought on by the recent price collapse will lead to significant shortfalls in supply and much higher prices in the medium term. Our constructive view on the outlook for oil and oil equities is largely driven by what we think is an unappreciated contraction on the supply side.

Subscribe to receive insights and updates from Antipodes

Subscribe to updates

Where to now for oil demand and supply?

Oil Demand

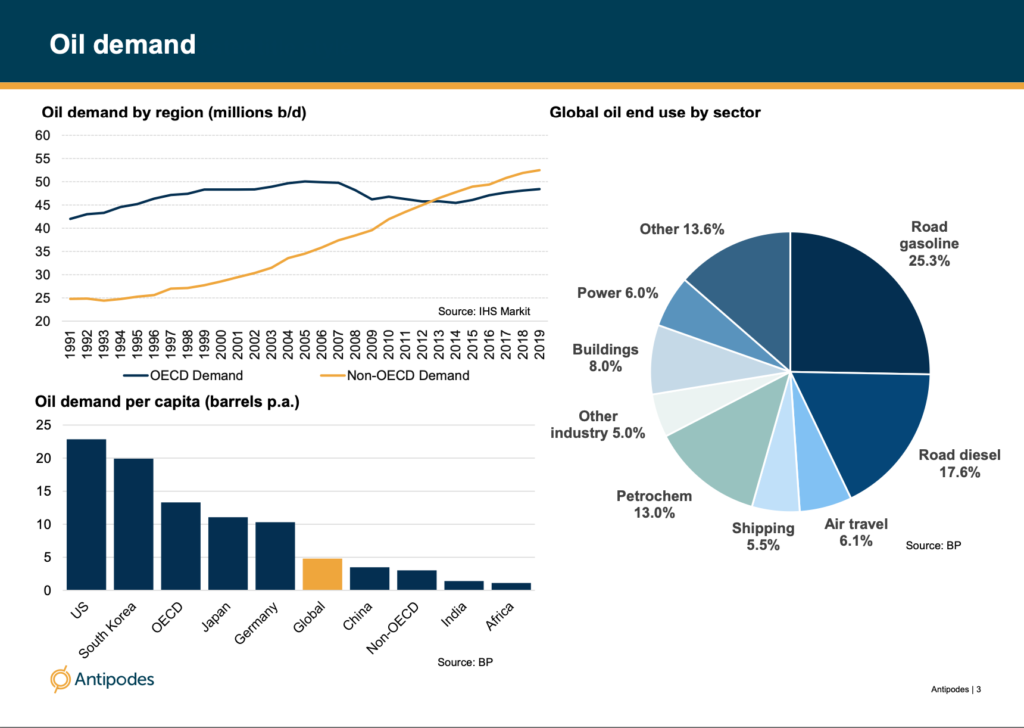

While improving energy efficiency and eventual electrification of the transport fleet will be headwinds, these shifts will happen over long periods of time and will initially be a developed market phenomenon.

Much is made of the threat to oil demand from Electric Vehicles however auto related demand is only around 30% of global oil demand.

Putting that into context, if one assumes that EV sales grow at 30%pa for next 10 years, the oil demand lost from the passenger vehicle fleet is only likely to account for roughly 2% of current demand. We also must bear in mind that decline will be spread out over 10 years and very much weighted to the end of the decade

Indeed improving energy efficiency and substitution of demand have been a common feature of the oil market for the last 50 years and yet over that time demand has grown at pretty steady rate of 1.5% pa, with little deviation from that trend over a business cycle.

In most parts of the world the convenience that comes from oil’s energy density and ease to transport and store is hard to replicate. The Non-OECD is now the largest constituent of oil demand and responsible for all its growth. With capita per consumption less than ¼ of what it is in the OECD there is still significant room for growth.

Just to illustrate that with some numbers, in the developed world we consume around 13 barrels a year per person. In China, that number is 3.5. In India it is 1.4 while for the entire continent of Africa it is 1. We think the outlook for oil demand is very much underpinned by developments in non-OECD countries.

Figure 1

Oil Supply

Supply is where we see the outlook for oil becoming interesting.

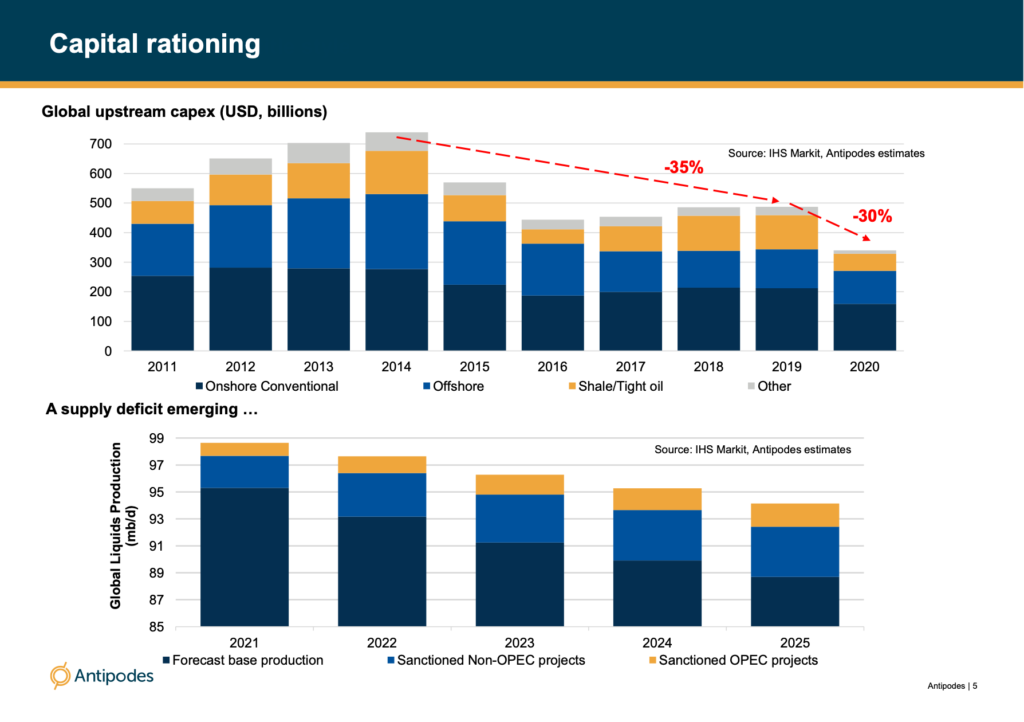

Over the last decade the world has grown production by around to 12 mb/d, with over ¾ of that growth coming from shale production in the US. So the desire to extrapolate that growth is understandable. It must however be noted that the rate of growth was only possible thanks to the willingness of capital markets to fund it. From 2010 to 2019 the industry spent around 125% of every dollar they took in operating cash. In absolute numbers that is about $100bn of outspend.

Even before the collapse in oil prices we were observing a significant shift in market behaviour with equity markets demanding significant FCF yields and funding for high yield and private operators largely shut.

Given the very high re-investment requirements for shale, underlying production is currently declining at 30%- cuts in capital spending have a very quick impact on production. This “treadmill” effect, combined with falling productivity was already resulting in production growth slowing significantly.

With capital investment in shale likely to be down 50% y/y, we expect to see a material contraction in US production over the next year.

The boom in the shale patch in the last decade has led to a severe rationing of capital for the rest of the market, leading to the delay and cancellation of many large conventional oil projects, especially in the last 5 years. In Figure 2, you can see an overview of capital expenditure across the wider oil industry. After peaking in 2014, we’ve seen a decline of around 35% and based on our internal analysis we are expecting another 30% reduction to global upstream oil industry capex in 2020.

Before the collapse in the price we also didn’t believe that the market had sanctioned enough large projects to offset the natural decline rates or the slowdown in shale with this year’s capex cuts only likely to exacerbate the future supply shortfall.

Figure 2

The outlook for oil

On the supply side, capital expenditure reductions in the oil industry that were being driven by tightening capital markets have been further accelerated by COVID-19. We expect this to set up an environment of global supply contraction over the next 5 years.

On the demand side, as we enter the COVID-19 recovery phase we will undoubtedly see economies and communities begin to normalise. The long-term track record of oil demand has been growth of about 1.5%, outside of macro shocks, such as the one we are living through today. We see future growth being underpinned by robust demand from non-OECD countries.

Given this supply and demand picture, we don’t think the current oil price reflects the outlook for oil in the long term.

Webinar

From out COVID-19 webinar series, Graham Hay and Jacob Mitchell discuss the outlook for oil and old and new energy.

This webinar was recorded on 7 May, 2020.